About Kollas Orchard

Education:

David: Oregon State University: BS; Cornell University: MS, PhD.

Janet: Central Connecticut State College: BA, MA.

Orchard History:

Seven acres of previously non-cropped land was planted 1976-79 using tree spacing of 6 or 8 feet in rows 7.5 feet apart. A one acre planting was added in 1993 with trees spaced 12 ft x 12 ft. Another 2.5 acres was set in 1998 at 12 ft x 12 ft. Current orchard area is about 6 acres, 1400 trees. Future plantings, using trees now in our nursery will include modifications based on our experience over the past 40 years.

Farm Retail Market:

Sales at the farm began with an unattended display under a small shed-roof in the

early 1980’s.

Father’s Early Advice;

“My father, an apple and pear grower in Oregon’s Hood River Valley, advised me to avoid orcharding: ‘Too much work, and you can’t make any money.’ Later, as Extension Pomologist for the fruit-growing industry in Connecticut, I saw that growers in New England faced more challenges than did those in Oregon (See note below). I decided to establish my

own ‘farm laboratory’ where I could innovate and evaluate, because I think orcharding problems exist to challenge human intellect.”

Current view of pear and apple orchards in Hood River, Oregon

- - - - - - - - note: The more humid climate of northeastern USA favors numerous fungal diseases that afflict apples and other tree fruits. Many of New England’s insect pests are absent, rare, or do not require routine control in the orchard districts of Oregon and Washington. And unlike their Pacific Northwest counterparts, New England growers typically operate their own on-farm refrigerated storage facilities, and most also have on-farm retail marketing.

“I think we may have a drainage problem here”

Outlook:

New England orcharding is an unusually challenging occupation. In the Kollas Orchard project I hoped to demonstrate that a family could profitably manage, in New England, an apple orchard with farm retail market; and that it could be done with little or no hired help. Knowing that such a project would require much hand labor, I thought I should design a system for labor efficiency. At Kollas Orchard I do not require ladders and I can get more done in a day of pruning, fruit thinning, and picking, and with less work. Physical labor is not the most tiring aspect of my orchard duties; rather it is the mental stress of seemingly never-ending decisions that must be made and acted upon quickly; that is what fatigues me. That, and insufficient sleep associated with frequent night-time spray applications, particularly in the Spring months. In the commercial New England orchards, diseases and other pests require frequent spray applications. Because orchard fruit is consumed as a food, spray materials and their application are highly regulated. The grower-operator is responsible for providing both high quality and safety in his harvested crop. Proper timing of spray applications is critical, and they must be made in favorable weather conditions to be effective. The decision-making involved requires familiarity with specialized knowledge and skills. Basic technical procedures such as conversion of units of measure, and the mathematics of spray calibration, for example, require a clear, rested mind that is alert to avoiding errors.

During the 40 years that I have operated an orchard there have been significant improvements in the tools available to growers: equipment, fruit varieties, clonal rootstocks, pest management, growth regulator options, irrigation, weather forecasts, etc.; not to mention the better understanding of plant growth processes that growers manipulate. But with these advances has come more complexity. If I, and others, spend another 40 years trying to outsmart the problems that can trouble and discourage orchardists, I think apple growing in New England will nevertheless remain one of the most difficult occupations that an intelligent and motivated person could choose. Finding ways to reduce complexity would help. That might be done by limiting the number of activities that require additional education or experience. For example, one might choose to only grow the crop but avoid or delay adding cold storage and retail marketing. Growers with science and engineering skills find abundant opportunities to apply those skills in orchards. Using such skills successfully in overcoming orcharding problems is highly satisfying, and builds self-confidence.

Pruning with pull-cut saw, electronic pruner, and snowshoes.

The rewards of owning and operating an apple orchard can make it especially appealing to some. Among the more positive features I include the opportunity to act with relative independence. One can set ones own goals, methods, and time constraints; and take responsibility or credit for the consequences. In my case, satisfaction derived from solving practical problems helps me justify the considerable time and effort that a difficult challenge may require. I also recognize advantages that can accrue to children of a farm family. And making one’s living by producing healthful and enjoyable food is an occupation in which one can take pride. The market for good apples is not likely to disappear. Somebody will be growing that fruit. The formidable qualifications required of aspirants to orcharding can be daunting. Rare is he or she who happily keeps ahead of all that must be done in an orchard business. It is no surprise then, the so many successful operations have a staff of several people, and less frequently only a husband-wife team.

Using a cart to move crates to the tractor in narrow alleyway

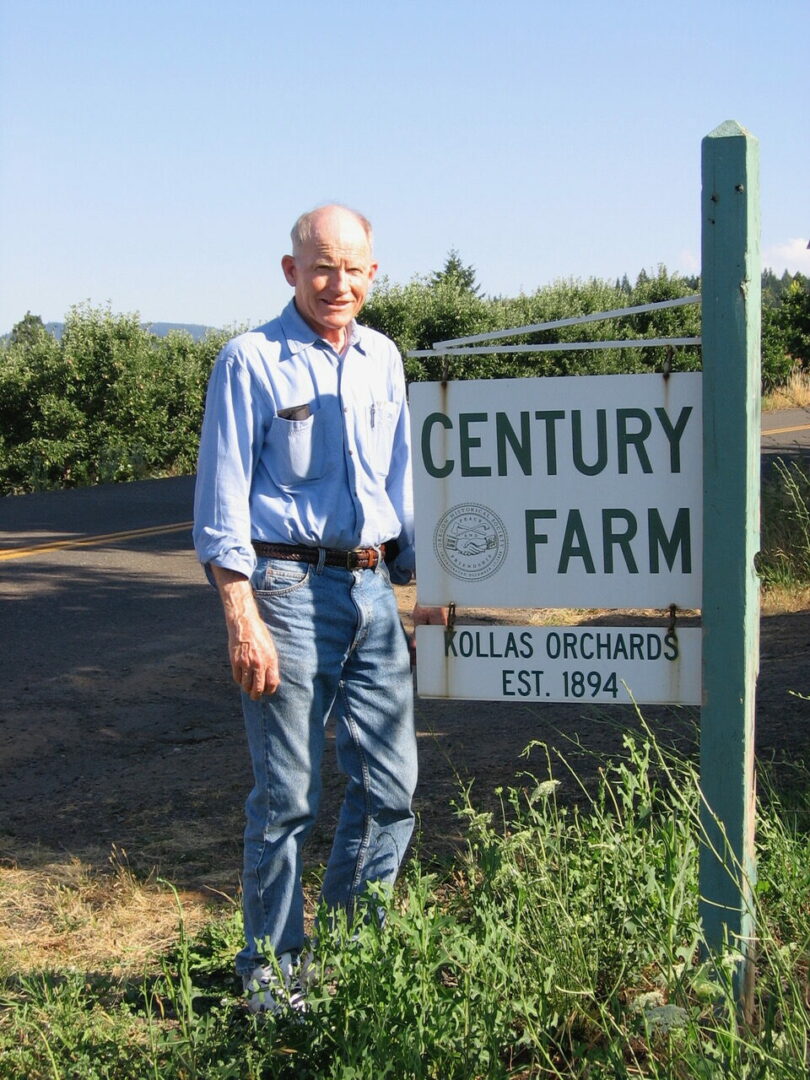

Visiting Kollas Orchards in Hood River, Oregon

As apple growing becomes ever more complex, success of single-operator farms, or even husband-wife teams becomes less likely. Thus the lone grower seems destined to be a rare bird in New England. However, pursued as a hobby, where profit is not a determining factor, apple growing will continue to be a reasonable option, as stress typically associated with commercial orcharding would be much reduced. If, additionally, high fruit quality were not a high priority, one could avoid use of regulated spray materials, eliminating much of the remaining stress of orcharding. In that situation the grower could happily focus on the abundant challenges that orcharding will continue to provide those who find nature incomparably fascinating, yet malleable.

Careers are often a consequence not so much of planning and expectations as of conditions not in our control, or just by chance and timing. That was true for my father. For me, acquiring an education that turned out to be marketable kept me in close contact with fruit growing and its problems. The problems drove me into an orcharding career, rather than away from it.

And it was my good fortune to find a wife who would accept the difficult lifestyle, and even find enjoyment in active participation! She especially loves keeping in touch with her customers and watching their children develop from infants to adults over the years. In my youth, even through my college years and beyond, I had no clear idea what my career would be. I wanted it to be interesting. It has been and continues to be that. I am happy with choices I made, and thankful for turning points along the way that were not in my control, but that nevertheless kept me on the right path.

Cheerful Janet on a Spring Day in the orchard

The Farm Store

Feeding a growing rock pile

In the Nursery

Keeping the crates clean

Preparing ground for new planting